Permanent Installations

For information about the exhibits or our gallery, please contact Gayle Lidman, Director of Public Programs and Community Engagement, glidman@jccsf.org or 415.292.1224. Please review the submission guidelines before submitting artwork.

First Floor

Right Direction Mezzuzah (Luigi Del Monte)

Right Direction Mezzuzah

Luigi Del Monte

Main JCCSF Entrance and Swig Family Beit Midrash

The name results from the design itself, which incorporates the concept of “the right direction” of mounting the mezuzah on a doorway. The rectangular base, when mounted, hangs perfectly vertical. The raised portion containing the parchment scroll slants, or inclines inward, toward the home, in “the right direction.” The raised portion reminds us of a compass needle which always leads us down the right path, visually reminding us of the concept of “the right direction.”

Prismatic Mezzuzah

Luigi Del Monte

Door Frames throughout the JCCSF

In a rainbow of colors of anodized aluminum, the Prismatic Mezuzah features uncluttered shapes with incised linear designs which maintain the symbolism and characteristics of the traditional object while showing the continuity of the tradition from ancient to contemporary life. The back closing panel is a real engineered work which securely protects the parchment. Each piece respects all the precepts of religious law.

About Luigi Del Monte

Luigi Del Monte is an Italian Jewish artist and engineer who specializes in contemporary art and design. Formerly a structural engineer, he launched a career in 1998 as a designer reinterpreting everyday and ceremonial objects in a contemporary style that pays homage to ancient traditions.

Del Monte initially focused on Jewish ceremonial objects, now in many of the world’s most important Jewish museums. His deep interest in Jewish culture and art manifests itself in the creation of fine Judaica executed with sophisticated, elegant lines and shapes, often incorporating the use of reflection.

His works can be found in the permanent collections of many prestigious institutions, including the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, the Spertus Museum in Chicago, the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles and the Museo dei Lumi in Casale Monferrato, Italy.

Sheva Middot

Sheva Middot

Sculpted Wall

Pottruck Family Atrium

In the spring of 2003, the JCCSF reached out to the community for inspirational quotations – Jewish or otherwise. Hundreds of submissions, spanning a wide range of religions, cultures, historical eras and subject matter, included everything from Bible passages to Gandhi to Muhammad Ali. Community leaders spent many hours working with a committee of local Jewish scholars and writers to make the final selections. The resulting seven core values and corresponding quotations are displayed on the 30-foot sculpted wall in the Pottruck Family Atrium. The wall includes Hebrew lettering, plus the English translations seen here. In addition to its visual beauty, the wall reminds JCCSF members, visitors and staff of the values at the JCCSF’s core.

The JCCSF’s Seven Core Values

Re-ut (Friendship):

Each of us bears the imprint

Of a friend met along the way,

In each the trace of each.

– Primo Levi

Hahnasat Orhim (Welcoming Strangers):

Let your house be open wide. – Pirkei Avot 1:5

Tikkun Ha-olam (Repair of the World):

How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world. – Anne Frank

Torah (Torah):

Torah. It is a tree of life to those who hold fast to it. Its ways are delight, and all its paths are peace. – Proverbs 3:17-18

Tzedek (Justice):

Until we are all free, we are none of us free. – Emma Lazarus

Klal Yisrael (Jewish Inclusiveness):

I make this covenant with all who are here this day and also with all who are not here. – Deuteronomy 29:13-14

Ruah (Spirit):

Not by might, not by power, but by my spirit. – Zechariah 4:6

Ruach – The Bridge of Breath (Joy Wulke)

Ruach – The Bridge of Breath

Joy Wulke

Aerial Sculpture

Atrium

Ruach connects the major features in the three-story, sky lit atrium. The Sheva Midot (seven principles), or word wall, containing key words defining the Jewish values, is connected to the donor wall by an aerial sculpture of suspended polished stainless steel arches with dichroic glass inserts. The work glints in the existing sunlight and changes character as the sun moves across the sky throughout the day and the various seasons of the year.

The work appears as the language of “breath” or ruach and is composed of two arches. The canopy of intersecting arches implies motion, movement of wind, past and present, light, and thought. This arch of sparkling light is a visualization of the connection of the current and future Community to the long-standing values that inspire its work, play, learning and action. The work invites your eye to look up and explore the volume of the architecture, through the skylights into the sky.

About Joy Wulke

Joy Wulke is a nationally recognized sculptor whose work bridges the boundary between visual art and architecture. Since receiving her Masters of Environmental Design degree from Yale in 1974, she has had numerous solo exhibitions and participated in group exhibitions in the United States, Europe and Japan. She has received numerous awards, including two Connecticut Commission on the Arts Artist Grants. Her commissions span the country and include work for Lincoln Center Film Forum in New York and The Louisiana Worlds Fair. Wulke is a consultant with the Connecticut Commission on the Arts in the Art in Public Spaces program. She is founder of Projects for a New Millennium, which has initiated collaborative projects in Connecticut, New York, Montana, Florida, and California.

The Kafri Menorah (Daniel Kafri)

The Kafri Menorah

In 1999 Linda and Sanford Gallanter donated the “Upright Menorah” by sculptor Daniel Kafri that stands in the JCCSF lobby on the first floor. Every year during Hanukkah, we light this beautiful bronze menorah daily at 4:30 pm. Everyone is welcome to attend.

Sculptor Daniel Kafri was born in Czechoslovakia in 1945. In 1949 he made aliyah (immigration of Jews to Israel) with his parents. He is a graduate of Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and a former teacher at Haifa University’s art department. In 1971 Kafri was awarded the prestigious First Prize in Sculpture at the Monaco Biennial. In 1976 he received the Jerusalem Prize for Sculpture.

His work has been commissioned by the Jerusalem Municipality, the Israel Prime Minister’s Office, and by corporations, hotels and individuals around the world. His sculptures have won many competitions, including one of American and Israeli artists, sponsored by the JCC of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His winning sculpture “The Menorah,” is displayed in front of the JCC Building in Pittsburgh.

Second Floor

Wall Drawing #446 (Sol LeWitt)

Wall Drawing #446

Sol LeWitt

Colored Ink Washes

Atrium, Second Floor, West Wall

Originally installed at Museum Haus, Krefeld, Germany

September, 1985

Installed at Jewish Community Center of San Francisco

May, 2005 by Sarah Heinemann, Paul Wackers and Matt DeJong.

A Gift of Doris and Donald Fisher.

The Digital Liberation of G-D (Heléne Aylon)

The Digital Liberation of G-D, 2004

Helène Aylon

Digital Interactive Installation

Beit Midrash, Second Floor

Helène Aylon inscribes herself in a long tradition of Torah commentators devoted to questioning and probing the words, and the spaces between the words, in the Five Books of Moses. Unlike prior commentators, she provides no answers. Her artwork poses questions, and invites her audience to enter its spirit of open inquiry.

Aylon has used a pink highlighter to draw attention to passages “where patriarchal attitudes have been projected onto G-d as though man has the right to have dominion even over G-d… between words in the empty spaces where a female presence has been omitted, where only the father’s name is recorded as the parent who begot the offspring; and over words of vengeance, deception, cruelty and misogyny, words attributed to G-d.”

While the original Liberation of G-d installation, now in the collection of The Jewish Museum in New York, served as a platform for national dialogues between the artist, viewers, and theologians, The Digital Liberation of G-d at the JCCSF is the first time viewers are able to study Aylon’s textual critique in depth: thanks to digital technology, they can read the entire highlighted Torah and respond to it by clicking on any of the pink highlights in the text on an adjacent commentary computer station.

About Helène Aylon

Helène Aylon is perhaps the only artist equally conversant in the ways of the Old World and the Art World. Born, raised and schooled in Boro Park, Brooklyn, at age eighteen she married an Orthodox rabbi and had two children shortly thereafter. She dutifully complied with all the rules and roles of the orthodox rebbetzin (rabbi’s wife) until the death of her husband in 1961. Meanwhile, Aylon studied art under painter Ad Reinhardt at Brooklyn College, and executed a mural commission for a Jewish chapel at New York’s Kennedy Airport. In the 1970s she returned to school to pursue graduate work in Women’s Studies at Antioch College West. Her artworks of the Seventies were process-based paintings made in such a way that they “changed with time;” the work of the Eighties was a feminist call for reverence for the Earth and an end to nuclear escalation and the Cold War. Only in the Nineties did she return to her own personal roots in Judaism, and take on the work of reconciling her soul’s principles with the language of the Torah. She has been highlighting the texts ever since.

Aylon has been the recipient of numerous fellowships and awards including two Pollock Krasner Foundation grants, a Yaddo MacArthur Foundation grant, several awards from the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council on the Arts, and the 2002 National Foundation for Jewish Culture Annual Visual Arts Award.

Her work is represented in numerous public and private collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Brandeis University Women’s Studies Center.

Curator’s Commentary

Scriptures that are the backbone of our People and that have withstood the test of the centuries come under new scrutiny when subjected to modern humanist appraisal. Add a feminist lens and the dissonance becomes more acute. What are we to do with this discrepancy? Ignore it or probe it? Treat the entire Torah as revealed text or dismiss the excesses of the past as historical artifacts? Between these two approaches lies a third path, one that takes the holy writings passed down from our forefathers as a point of departure for what it means to be a Jew today, and what Jewish values might be in the light and shadow of our heritage.

Peter Samis

Assoc. Curator of Education

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Project Curator

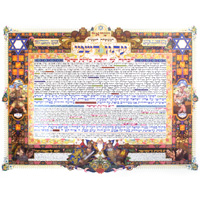

Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel

DECLARATION OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE STATE OF ISRAEL

Arthur Szyk

Second Floor

This historic proclamation is illuminated in numerous colors in Arthur Szyk’s renowned medieval manuscript style. Miniature vignettes of Jewish history and the newborn State of Israel surround the central Hebrew text of the Declaration. Images include the pioneer (halutz) who sows the land; the soldier who defends the land; Moses with his brother Aaron the High Priest and the warrior Hur; Ezekiel, the prophet who called for restoration to the Land; skulls and bones as a reminder of the Holocaust; King David, the first King of the Jewish People in Jerusalem; and the symbols of the twelve tribes of Israel.

In her memoirs, his wife Julia Szyk records that the day the independence of the Jewish state was declared her husband wept and then sat down to create this masterwork, devoting more than six months to its completion. It is said that this very work and his completed Declaration of Independence of the United States hung side by side in the Szyk household until his death in 1951.

About Arthur Szyk (June 16, 1894 – September 13, 1951)

Arthur Szyk was a graphic artist, book illustrator, stage designer and caricaturist. He was born into a Jewish family in Łódź, in the part of Poland that was under Russian rule in the 19th century. From 1921, he lived and created his works mainly in France and Poland, and in 1937 he moved to the United Kingdom. In 1940, he settled permanently in the United States, where he was granted American citizenship in 1948.

Szyk became a renowned graphic artist and book illustrator as early as the interwar period – his works were exhibited and published not only in Poland, but also in France, the United Kingdom, Israel and the United States. However, he gained real popularity through his war caricatures, in which, after the outbreak of World War II, he depicted the leaders of the Axis powers. After the war he also devoted himself to political issues, this time supporting the creation of Israel.

Szyk’s work is characterized in its material content by social and political commitment, and in its formal aspect by its rejection of modernism and drawing on the traditions of medieval and Renaissance painting, especially illuminated manuscripts from those periods. Unlike most caricaturists, Szyk always showed great attention to the coloristic effects and details in his works.

Third Floor

Jerusalem, Holy City II (Amram Ebgi)

Jerusalem, Holy City II

Amram Ebgi

Limited Edition Hand Colored Etching with Intaglio Relief

Third Floor

Jerusalem the Holy City II features a view of the old city from Mount Scopus. Embossed in intaglio relief in the background of the work are the words “Me’al Pisgat Har HaTsofim: From the Summit of Mount Scopus.” These are lyrics to a treasured Israeli song.

Written in 1928 by poet-lyricist Avigdor Hameiri, it was inspired by a 1880s Yiddish folk song by Borech Shafir. The music was adapted from a Polish aria written by Stanislaw Moniuszko.

Over the years (long before the 1967 Six Day War and the reunification of Jerusalem) the song became canonized and obtained the status of the premiere Hebrew song celebrating Jerusalem until Naomi Shemer wrote Jerusalem of Gold in 1967. It has still retained its status as a classic anthem.

About Amram Ebgi

Amram Ebgi was born in Morocco in 1939. He immigrated to Israel in 1951 and lived in a small kibbutz Kfar Blum. Ebgi began drawing and painting at age 16 and in 1958 received a scholarship to study art at Brooklyn Museum of Art. In 1962 kibbutz administrators, recognizing his talent, gave him a painting studio and encouraged him to sell his works. Ebgi stopped his art to fight in the Israeli Six Day War. Ebgi continued art study at Pratt Graphic Art Center in New York, where he developed a love for printing; etching, silk screen, intaglio, relief and epoxy modeling.

In 1981 Ebgi relocated to Miami, Florida where he currently has a studio. He has enjoyed one man shows throughout the US and Israel. His work is collected by private and public institutions and museums throughout the world.

An average work takes two months to create with some being composed of as many as 60 separate elements or pieces. Yet, when finished, each work is like a masterful symphony orchestrated by a perfect team of musicians – a meticulous shimmering blend of design and color. This versatile artist also works in many other media including oils, watercolor, stained glass, ceramics, woodcarving and more.

Curator’s Commentary

Scriptures that are the backbone of our People and that have withstood the test of the centuries come under new scrutiny when subjected to modern humanist appraisal. Add a feminist lens and the dissonance becomes more acute. What are we to do with this discrepancy? Ignore it or probe it? Treat the entire Torah as revealed text or dismiss the excesses of the past as historical artifacts? Between these two approaches lies a third path, one that takes the holy writings passed down from our forefathers as a point of departure for what it means to be a Jew today, and what Jewish values might be in the light and shadow of our heritage.

Peter Samis

Assoc. Curator of Education

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Project Curator

About the Lyricist Avigdor Hameiri 1890 – 1970

Avigdor Hameiri was born in a small village in Hungary, where he received a traditional Jewish education. From 1905 he studied at the high school associated with the (state-run) Budapest Rabbinical Seminary. While still an adolescent, he became actively involved in the Zionist cause and wrote for the Hungarian press. His first poem was published in 1909, and his first poetry anthology appeared in Budapest in 1912, arousing much interest.

In the summer of 1914, Hameiri was conscripted into the Hungarian army, becoming a commissioned officer in World War I. For approximately two years he fought in Galicia against the Russian army and at the end of 1916 was captured. For six months he was transported to, and tortured in, various prison camps in Asiatic Russia, until he was set free in February 1917 as a result of the Russian Revolution. He swiftly made his way to Kiev and from there to Odessa, where he was warmly welcomed by the circle of Hebrew writers there, who helped him resume his Hebrew writing career.

In the summer of 1921, Hameiri left Odessa with a group of writers who were permitted to leave Russia, and later that year he immigrated to Palestine. He spent most of his remaining years in Tel Aviv, where he dedicated himself to literary work, theatrical productions, and a wide variety of journalistic activities. Among other achievements, he established and managed the first Hebrew satirical theater, Ha-Kumkum (The Kettle), which from 1927 staged satirical cabarets based on the Central European model. After the establishment of the State of Israel, Hame iri worked as an editor and recorder at the Israeli Knesset.

Avigdor Hameiri was one of the original 16,000 freedom fighters in 1948. He published the State’s first independent newspaper and helped to organize the worker’s bank. His book Hannah Senesh is an obligatory reading for all Israeli school children. Hameiri was the first poet to whom the title Israel’s Poet Laureate was awarded.

Hameiri fought in World War I in the Austro-Hungarian army and recorded the events in his memoirs, The Great Madness (1929) and Hell on Earth (1932). His books have been published in 12 languages.

His poem, “Me’Al Piscat Har Hatsofim,” reveals his love of the land and the quest for peace, intrinsic in the early Zionist spirit.

He died in Israel on April 3, 1970.

English Translation of Lyrics

ABOVE THE PEAK OF MT SCOPUS

Above the peak of Mount Scopus

I will bow down to the ground to you,

Above the peak of Mount Scopus

peace to you, Jerusalem

For a hundred generations I dreamt of you,

to cry, to see the light of your face.

Chorus:

Jerusalem, Jerusalem

light up you face to your son,

Jerusalem, Jerusalem

from you ruins I will build you.

Above the peak of Mount Scopus

peace to you, Jerusalem

Thousands of exiles from all parts of the world,

lift their eyes to you

thousands of blessings,

be blessed, as a king sanctifies a royal city.

Jerusalem, Jerusalem

I won’t move from here,

Jerusalem, Jerusalem

the Messiah will come, will come.

The Jewish Wedding (Bernard Zakheim)

The Jewish Wedding

Bernard Zakheim

Fresco

Third Floor/Roof Landing

In the early 1930’s, Zakheim was known as an interpreter of Jewish life and an advocate for Yiddish culture. He was an organizer of the Yiddish Folkschule on Steiner Street, where he taught children’s art classes and organized the first “Yiddish art” exhibit in San Francisco.

The original site for the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco’s (JCCSF) mural was an idiosyncratic architectural space-a twelve-foot arch in an open-air courtyard. This space presented a unique challenge, which Zakheim resolved with a dynamic composition of an ancient wedding celebration. The wedding scene is an imagined one; while it appears to be set in ancient times, the distant cityscape looks medieval. The various figures in the mural suggest diverse origins in their features and dress – some appear African, Middle Eastern, Asian, or European. This reflects the artist’s inclusive vision and the progressive spirit of the 1930’s. It also mirrors the Centers commitment welcoming people of all backgrounds.

The wedding celebrants are vividly depicted and the forms of the musicians, dancers and archers are characterized by movement. Women and men are gathered together in a semi-circle around a drumming figure; whose instrument is adorned by the artist’s signature both in Hebrew and in English.

The imprint of Zakheim’s Hasidic upbringing-with its emphasis on music and dance as a form of joyful prayer-and his years of preparation for the rabbinate, are clearly felt in the mural’s integration of context, figures and text.

Three rabbis and the wedding couple, an athlete and maiden, are gathered under the chuppah (wedding canopy), which signifies and literally frames the wedding ceremony. Its flowing canopy is anchored by the Star of David, which draws our eyes to the Hebrew text from The Song of Songs.

Zakheim employed the ancient art of fresco, or affresco (Italian: fresh) – painting on freshly laid lime-plaster ground, to create the painting. Pure powdered pigments are finely ground, then dissolved only in water and applied directly to the wet plaster (intonaco). The colors are absorbed into the surface of the plaster and a chemical reaction occurs – the carbon dioxide in the air combines with the calcium hydrate in the wet plaster, forming calcium carbonate. The colors solidify and become one with the plaster as it dries, becoming an integral part of the wall.

The brilliant white of the lime plaster and the purity of the pigments (no binder is added, as in oil, egg tempera and other paint media) create a luminosity and subtle matte surface unique to fresco. True fresco is a most direct method; once the color touches the wet plaster, the mark is there to stay – erasure, corrections and over-painting are nearly impossible. Zakheim had to work rapidly and surely, completing each new section on freshly laid plaster in one day’s work. He recognized that the difficulties and limitations of the fresco process are also its strengths – calling for a simplicity of painterly handling, strength and clarity of form, a subtle and harmonious palette of perfectly soluble earth colors.

In her book Coit Tower, San Francisco, Masha Zakheim says her father “likened the application of the brush on wet plaster to the bestowal of a kiss.” The couple standing in the foreground of the mural reflects this awareness – they have been given the most sensitive painterly treatment. The two figures are distinguished by their delicate beauty and dignity. Their identity within the narrative is not known, yet they have a compelling presence and convey an intimate relationship.

About Bernard Zakheim

A pioneer of the Bay Area mural movement of the 1930’s, Bernard Baruch Zakheim (1896-1985) Zakheim was born in Warsaw, Poland to a family of Hasidic Jews. He was training to become a rabbi, when at age thirteen; he defied family and religious traditions by announcing his intention of becoming an artist. His mother’s fierce objections led to a compromise-Zakheim attended a school of applied art and trained to become a furniture designer and upholsterer. His desire to become an artist persisted-he studied privately and then was awarded a scholarship to the National Academy of Fine Art, where he studied drawing, painting and sculpture.

As a young man he closely followed the Russian Revolution, and became active in the drive for Polish independence. He and his wife emigrated to the United States in 1920, settling in San Francisco. Zakheim founded a successful furniture company here and pursued his art practice on the side, but over time he became increasingly frustrated with this situation. In 1930, inspired by the art and politics of Diego Rivera, he sent some of his drawings to the artist. Rivera responded by inviting Zakheim to visit him in Mexico. There, Zakheim discovered the twentieth century’s great revival of fresco technique-the Mexican mural movement led by Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros. Regarding Zakheim’s sketches, Rivera commented, “every artist puts into his work something of his own soil, of his own people.” In 1932 Zakheim traveled to France, immersing himself in the artistic community and surveyed the work of the European modernists. He continued on to Italy and Hungary, where he studied fresco technique. Zakheim’s first fresco, Jews in Poland, a historical representation of Jewish life in Warsaw, was painted in Hungary. A watercolor study is all that remains of this important early work (the site of the fresco, an 18th century Protestant church, was partially destroyed in 1939).

Zakheim returned to San Francisco in 1933, and learned of the JCCSF’s plan to commission a local artist to create a fresco for their new building. In response to Zakheim’s urging, an open competition-rather than the planned direct commission-was held, and Zakheim’s proposal was selected.

The legacy of Bernard Zakheim’s art has shaped the lives of his children and grandchildren. The restoration, removal and reinstallation of the JCCSF mural was led by his son, Nathan, himself a renowned art conservationist who is widely recognized for developing innovative methods for safe removal of large frescoes.

In its original site in the courtyard of the old JCCSF, the fresco was exposed to the elements, and the mural’s surface – its very substance – was suffering erosion. In 1976, with Bernard present to advise, Nathan and his brother Matthew carried out the first of it’s restorations.

When the mural was removed from the old building, Nathan called upon his three sons for assistance. Kuva, Kirti and Dhanan joined their father in the complex process of removal, conservation and reinstallation of their grandfather’s mural. After meticulously cleaning the surface and putting a temporary protective varnish on it, a large drawbridge was prepared to support the mural as it was to be removed from the wall. A plywood and steel crating system was devised to transport the fresco safely. When the mural was reinstalled in its new home, it was partially conserved “in situ” by Nathan, assisted by Julia Luke, using pigments to “in-paint” the lost and faded details and restore the color saturation to its original level. Visitors now have the opportunity to see this mural, originally painted in 1933, fully restored and bathed in natural light.

Videos:

Nathan Zakheim: Excellence in Art Conservation

The Murals and Art of Bernard Zakheim

The restoration, reinstallation and celebration of the Zakheim mural was generously funded by the Fleishhacker Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.